Out of the Blue

On a jungle-shrouded private island in Fiji, the world's most extravagant resort.

Originally published in Travel + Leisure, March 2015

SUPPOSE YOU WERE TO BUILD YOUR OWN RESORT—on a remote Fijian island, say—and money were no object. Common sense not a factor, either. Maybe you don’t even need people to come. Maybe you’d be content to use the place yourself, with the occasional paying guest, and only a distant chance that someday you’ll break even. What might that place look like? And what would you put there?

Perhaps you’d put in an 18-hole golf course, then hire a team of 32 just to maintain it. You could add a couple of restaurants—no, how about five restaurants?—that would each stay open every night. You’d want a state-of-the-art airstrip and a pair of planes trimmed in leather and burled mahogany. Definitely a marina or two. And maybe there’s another island a mile west, where you’d build an entire village from scratch just to house your staff, using three ferries to shuttle them back and forth.

If you’re really feeling ambitious, you could add a 240-acre farm with plots growing six varieties of mango and 10 types of tomato; orchards of avocado, papaya, and passion fruit; flocks of Fijian sheep and heirloom chickens; and your very own herd of Wagyu cattle. Of course the island would be covered in coconut palms, all bursting with fruit—so much of it that the spa would make its own line of coconut-based massage oils, and butlers could even draw guests a bath of coconut milk.

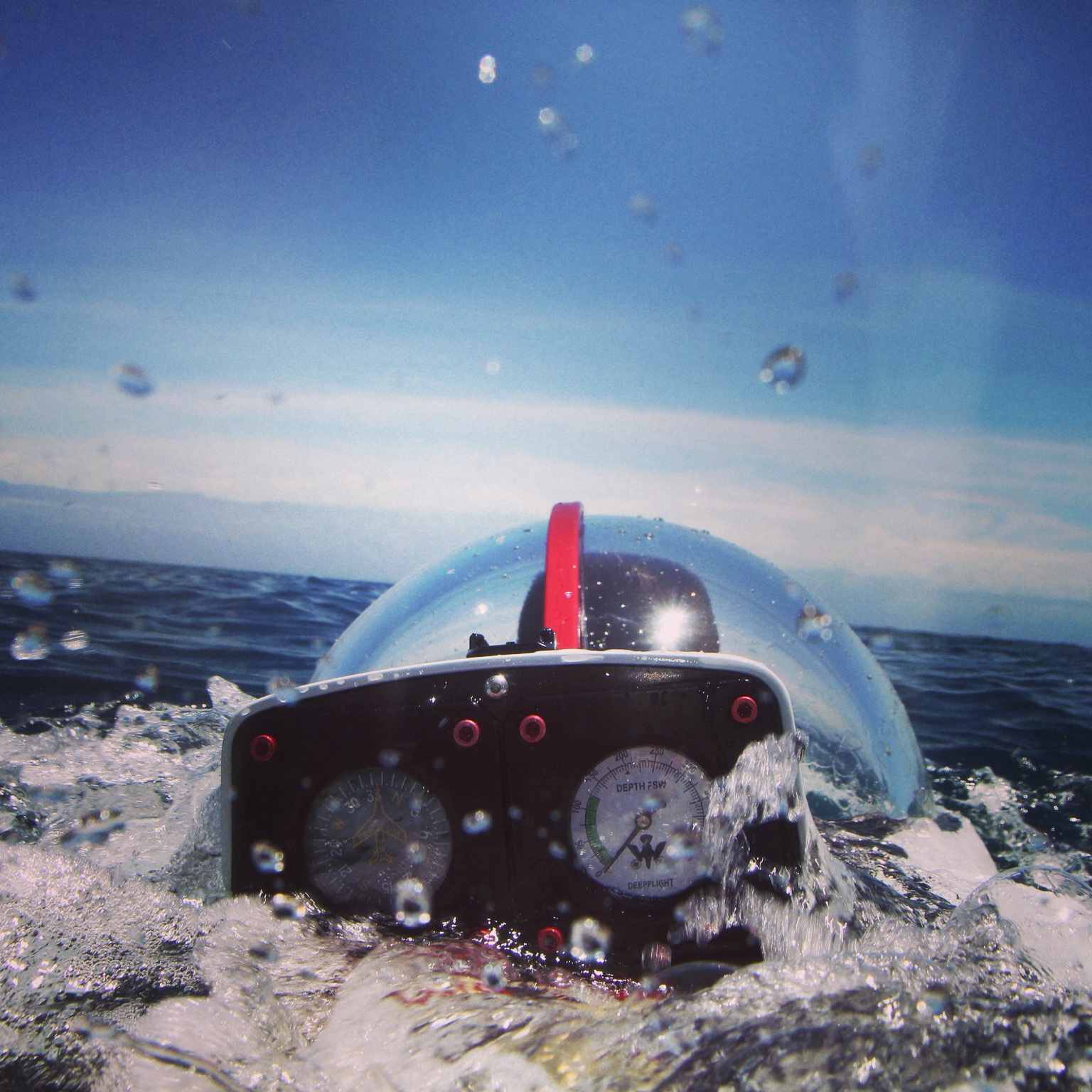

But why stop there? Maybe you could buy a submarine—an actual submarine, straight out of a Tintin comic!—for surreal rides among the rays and reef sharks and hawksbill turtles right offshore. (Clincher: there’d be no extra charge for sub rides.)

If all this sounds like your kind of crazy, then you’re going to love Laucala.

Located in Fiji's northern archipelago, an hour’s flight from Nadi International Airport, Laucala (pronounced “lo-THA-la”) is a 3,500-acre private island that might as well be a private alternate universe. It is the brainchild of Austrian billionaire Dietrich Mateschitz, cofounder of Red Bull energy drinks. He bought the island in 2003 from the estate of Malcolm Forbes, who’d used it as a personal getaway since 1972. (Forbes’s ashes are buried on the island, under the inscription "When Alive, He Lived.")

Building off the Forbes estate—set within a former coconut plantation—Mateschitz spent five years and untold millions creating a 25-key, ultra-luxe resort. Laucala finally opened in 2008, charging rates only a mogul (or Mateschitz himself) could afford. Villas—which come with free-form infinity pools, private dining pavilions, and hulking stone bathtubs, each as big as a sarcophagus—start at $4,600 per night, all-inclusive, though about half are priced between $6,600 and $9,600. (The three-bedroom Hilltop Residence goes for $44,000 a night, which could explain why in six years it’s been booked only a handful of times.)

For all the man-made excess, Laucala’s natural beauty is equally extravagant. Most of the island is given over to jungle-draped volcanic peaks; forests of pandanus, sandalwood, and mahogany; coastal mangroves; and long, empty beaches framed by lagoons and the sparkling Koro Sea beyond. Abundant tropical foliage—frangipani, heliconia, torch ginger—means Laucala is especially rich in birdlife, including white-collared kingfishers, collared lories, and the rarely glimpsed orange dove, with plumage like a ripe persimmon. It is, in short, exactly the island you’d choose if you were looking to buy one yourself.

Mateschitz is among a small group of island-owning impresarios that includes the late Laurance Rockefeller, Richard Branson, David Copperfield, and Larry Ellison. Unlike those men and their islands, Mateschitz keeps an exceedingly low public profile, and Laucala operates with a seemingly total disregard for profit. If non-Austrians know the name, it’s likely because Mateschitz was the moneyman behind skydiver Felix Baumgartner’s 23-mile leap from near-space in 2012. Or because he owns four soccer clubs, a nascar team, and two Formula One teams. (He also collects vintage airplanes.) The 70-year-old has a Bransonian flair for adventure and expensive toys along with an air of mystery befitting Charles Foster Kane.

Mateschitz has always been a business iconoclast. Ignoring market research that said Red Bull tasted terrible, he forged ahead and built an empire. To Laucala he’s brought the same damn-the-torpedoes attitude. For its first few years, Laucala hovered quietly under the radar, as its publicity-shy owner seemed to prefer. Lately, however, the resort has gained exposure and momentum as Mateschitz has bankrolled extensive upgrades to the property and made some flashy acquisitions, like that $1.85 million submarine. Last year, he even coaxed Aman Resorts’ longtime director of operations, Andrew Thomson, to come aboard as general manager. (It’s a homecoming of sorts for Thomson, a fifth-generation Fijian.)

Why the sudden amping-up of ambition? Perhaps Laucala’s patron realized that it would take even more money, and a bit more horn-blowing, to rise above the scores of luxury beach resorts in the world—or at least to justify prices that are two to three times more than they charge. (Only North Island, in the Seychelles, with villas averaging $6,700 a night, comes close to Laucala.) Or perhaps it’s just that Dietrich Mateschitz doesn’t do half measures. “He wants this to rank among the finest resorts on the planet,” Thomson said of his new boss. “And he’s sparing no expense in making that happen.”

The numbers would make an unseasoned GM blush. Laucala employs a staff of 385, including 32 full-time gardeners, five dedicated coconut pickers, and a team of seven to attend to the island’s 32 pools. (For those counting at home, that’s a staff-to-guest ratio of 8 to 1. And this assumes all villas are occupied, which is almost never the case.) The property makes its own honey, tamarind jam, and lemongrass candles; raises pigs and quail and ducks and the aforementioned Wagyu beef; even grows its own orchids—3,500 of them—in a vast greenhouse. Fully 85 percent of Laucala’s food is produced on-island.

It is not, on the surface, an altogether rational endeavor. Laucala is rather like something you might have hallucinated in a fever dream after a long night guzzling Red Bull—and then, to your accounting team’s mounting alarm, went ahead and built.

So who actually goes to Laucala? The week my wife and I visited, the guest list was like the setup for a joke: two honeymooning Kuwaitis (they were 22, if that), a Russian couple celebrating their anniversary, two regal-looking Germans, and a group of Hong Kong traders who’d heard about Laucala from Steve—son of Malcolm—Forbes himself. “Steve and I had lunch, and he suggested we come,” one of them told us. “Though apparently even he can’t afford it anymore.” (We paid a press rate, which made it a whole lot more affordable.)

The week prior, I learned, one villa had been occupied by a couple from Kazakhstan, who were dismayed to learn that Laucala’s 3,800-foot airstrip could not accommodate their private jet. (It was a 767.) Reluctantly, they consented to park the plane in Nadi and ride Laucala’s seven-seat Beechcraft turboprop to the island.

It’s not all oligarchs, emirs, or oil barons from former Soviet republics; the majority of Laucala’s guests are in fact Americans, albeit extremely rich ones. But in truth, one seldom encounters other guests. The resort’s 25 villas are widely spread out across the north coast—along the beach, on a forested plateau, or on private seaside bluffs—and well concealed from their neighbors. We saw our housekeepers (who came three times a day, delivering fresh-squeezed juices, fruit platters, and canapés at each visit) more than we saw the Kuwaitis, Germans, and Hong Kongers. That left only the Russians, to whom we spoke just once. Turns out they’d been married at Laucala the year before, and planned to return for every anniversary. They’d invited no friends or family to the wedding, the wife told us, only a crew of six videographers to document their every move. For a week.

If you’re bent on filming your own reality show, Laucala offers dozens of stage sets you might have all to yourselves. Like the Rock Lounge bar, a cliff-top aerie with miles-long views from chaises clustered around a fire pit. At any other resort, this bar would be packed all night long. But every evening that we stopped in for cocktails, we were the only guests. Joeli Vuadreu, the lone bartender, was always comically excited to see us. “It gets a bit lonely,” he admitted while polishing the glassware for what must have been the 19th time; there are weeks when Vuadreu hardly sees a soul. Yet each night he shows up for work, wipes down the teak bartop, cues up the music, and lights the torches and the fire pit, on the off chance someone might show up.

This sort of practice would drive a corporate efficiency expert nuts—but then Laucala is the furthest thing from efficient. A normal hotel, for instance, might ask if certain projects are worthwhile. Is it a sensible investment of time and resources to plant an orchard of 50 vanilla vines, which now require a Laucala staffer to spend several hours each morning pollinating hundreds of flowers by hand, using a toothpick? But such questions—Is this worth doing? Should we even bother?—do not apply here. At Laucala, the default answer is: Of course.

Anthony Healy, Laucala's Executive Chef, showed us the vanilla-pollination trick himself. It was delicate, frustrating work, like threading a needle covered in sap. It’ll be six months before the beans can be harvested, and another year before they will be ready to use.

Healy was leading us on a farm tour, one of Laucala’s most popular activities. The island grows 40 different vegetables (including beets, taro, okra, and eggplant), 15 fruits (pineapple, guava, gooseberries, soursop), countless herbs, hydroponic lettuces and microgreens, even coffee, tea, and sugarcane. All of them are under organic cultivation.

Farther south is the livestock farm, whose Sulmtaler chickens—brought in from Austria—lay eggs with yolks as vibrant as an orange dove’s feathers. The Wagyu herd now numbers nine, up from the original four bought in 2013 for $150,000. The cattle graze in the lushest pasture you can imagine, under incongruous stands of coconut palms. (While Laucala’s ambition for food sustainability is undeniably impressive, the resort is not exactly a green operation: it burns through more than three tons of shipped-in oil per day.)

From the paddocks we circled around the south coast, bouncing down a dirt track through ever-thickening jungle. This was the untouched side of the island. Two wild goats scampered off into the woods, and Healy briefly considered giving chase. “My crew likes to catch them and make goat curry,” he said, hungrily. Healy pointed to the reef just offshore, where he and his chefs had gone free diving the day before. They’d brought up a dozen lobsters, which would be on the dinner menu that night.

The food is a high point. I loved the fresh-caught tuna sashimi at Beach Bar, breakfasts of silky congee and those golden-yolked eggs, and the quasi-secret, six-seat teppanyaki restaurant that clings to a cliffside above the sea. All five restaurants really do stay open every night, even when only one couple is in residence. Guests can also dine in their villas, and some do so for every meal. But we kept returning to Seagrass, Laucala’s Thai restaurant, run by chef Piak Sussadeewong, formerly of the Mandarin Oriental Bangkok. Piak’s prawn salad with palm hearts and fiery gai toey (fried chicken with pandanus leaves) were among the best renditions I’ve had.

Days at Laucala are spent snorkeling among the hawksbills, paddling the lagoons on an outrigger canoe, and game-fishing on the Riviera Flybridge yacht. There are hikes to nearby waterfalls and long rides along the beach on Laucala’s resident Fijian horses, a sturdy crossbreed of Clydesdale and Australian Thoroughbred.

And if you want something more adventurous, there’s always the submarine. The DeepFlight Super Falcon Submersible is more fighter jet than sub, in both looks and performance. It is 22 feet long and shaped like a Star Wars X-Wing—the pilot sits in front; you ride in back, like R2-D2. It can dive to 400 feet. It can barrel-roll. It can go six knots per hour, which isn’t all that fast, but certainly feels so when you’re flying—the only word for it—through the ocean, darting among the coral like a high-precision drone.

For now, the Super Falcon is launched from shore using a beach-loader, and travels only inside the reef at an average depth of 25 feet. But Laucala is considering buying a new boat that could launch the sub in the water, allowing for excursions well beyond the reef—to the famous Great White Wall, for example, one of Fiji’s top dive sites.

Given the scale of investment and the talent involved, it’s no surprise that Laucala is incredibly well-conceived and well-run—though its understated style does come as a surprise. (At resorts with unlimited budgets, decorative restraint is rare.) I’d arrived expecting something absurdly over-the-top. I was prepared to be disoriented, if not outright put off, by the idea of so much being spent for the enjoyment of so few. That feeling did creep in on occasion, but Laucala mostly manages to come off as an entirely natural, almost normal undertaking. (Even the fine-dining restaurant, with its $100-a-piece Robbe & Berking flatware, feels unassuming and relaxed.) This is, in essence, a place where the über-rich can go to pretend money doesn’t matter, all while spending massive amounts of it. They can believe they’re invited houseguests on the proverbial island of the lotus-eaters, residents of a sovereign principality governed only by the rule of Yes.

The question of whether Laucala turns a profit (currently a definite no) is for now of little consequence, one manager told me—and why would it be? Even beyond his $7 billion net worth, Mateschitz has no board of directors to answer to, no brand managers to appease, and no reason not to indulge every whim and desire. In that respect, he’s the embodiment of his resort’s clientele. For jaded plutocrats, Laucala provides a sure-fire cure for ennui. For the rest of us, it offers an anthropology lesson in what the super-wealthy seek now: extreme privacy, unbridled freedom, and an outwardly wholesome breed of luxury, couched in notions of eco-friendliness and sustainability (while not entirely adhering to either).

“What we’re trying to achieve here doesn’t follow any recognized business plan,” Thomson told me, perhaps stating the obvious. When Thomson took the reins last January, he was constantly asking himself, How on earth does this work? “And there’s no real answer to that,” he added, “except that this is Mateschitz’s home, and he’s extremely keen to see it get better and better.”

Mateschitz, who lives primarily in Austria, spends only about a month per year at Laucala. But the rest of the time he’s still a constant presence around the resort, his name invoked in whispers by employees and guests alike: this reclusive, Hearst-like figure with his toy Fijian island. Of course Laucala is much more than Mateschitz’s toy. It’s clearly his passion project—a series of grand experiments in agriculture, design, self-sufficiency, and logistics, and one its patron might very well keep pursuing even if all his guests were to someday up and leave. In the meantime, for those who can afford it, the club is open. •